The introduction to Golden Hammer that appears in the printed version was written by my father in 1961, and briefly states “S.E. Ellacott worked in our Foundry for a time and later became a Schoolmaster, Author and Illustrator, so he was an obvious choice to write this book.”

That was it, done and dusted, let’s move on - well no. actually Mr Ellacott really deserves a bit more of a mention and so this page centres on his involvement and connections with Garton & King Ltd which go far beyond his authorship of the 1961 publication and the creation of some 15 or so illustrations, even though the foundations of the history had been laid down back in 1939 by Nancy Lovely – see the 1939 Notes.

Much information has been gleaned about S.E. Ellacott and with permission has been reproduced on this page. The source was a 2016 publication entitled ‘A Peerless Gentleman’ written by David Poulter, a close friend. It traces his life from birth in 1911 through to his death in 1997. ISBN 978-0-9572149-9-6

Oswald Ernest Ellacott was born in Winkleigh on the 20th May 1911 and christened with these names some four weeks later. His first name he came to loathe, answering only to Os, later settling for Samuel after his mother’s stepfather. Not until 5th January 1950 was his name eventually changed by deed poll to Samuel. As a young lad he showed an ability to grasp and retain information; always ready to learn and to learn thoroughly and content only with answers to the multitude of questions he raised within the family and elsewhere and in time those around him often remarked ‘he knows his own mind.’

He was always keen to know how things worked, showing interest and curiosity and absorbing what he was taught. Outside of school he discovered the intricacy of the wheelwright’s craft and the skills of the blacksmith where he was shown, amongst other processes, how to heat, quench and re heat metal to build strength without brittleness. He developed also a deep familiarity with nature and wildlife. One can but refer the reader to the book described above in the second paragraph to fully understand his formative years and experiences – all of which culminated eventually in him realising his long held wish and desire to become a schoolteacher, a profession he held from 1947 through to 1971.

His abilities and desire to further his education lead him to being accepted at the University College of the South West of England, this meaning living in Exeter and earning enough money for the fees and to contribute where possible to his parents meagre income. This was probably 1926. His overriding interest at the University College was History, followed by English Language and Literature, then Geography and Art. Part time jobs helped provide the necessary funding, butchers boy, mixing paint & wallpaper paste, and work at the Mayflower Dairy and meeting the requirements to serve in a Chemist’s shop. Completing crosswords in national newspapers provided a regular, if unexpected, income. Regular visits to the Cathedral library also helped strengthen his weaker subjects and also to pursue his passion for Military History.

His skill at drawing progressed, equipped with pencil pad, eraser and his bone handled knife he recognised there was much to sketch and record within the city, be it people, animals or buildings. His father, Ernest had carried the knife throughout his service in the war and had gifted it to Sam to become one of his most treasured possessions.

It is here we must recall Sam’s introduction to Garton & King, an essential part of this page, and I have extracted the following from the book.

The shops in Exeter, many of them Elizabethan, obligingly presented their intricate facades and he had filled half a dozen pages of his sketch book before noticing a large gold-painted hammer hanging high from a rather plain-looking shop front. Intrigued, he investigated the unlikely object. Behind the tall rectangular windows which flanked the doorway were displayed iron stoves, large and small, iron gratings, pots and pans and other kitchen utensils. Above the fascinating hammer, in large square lettering, were the words “GARTON AND KING, SANITARY ENGINEERS”. It was the showroom for that company’s Iron foundry, which Os discovered around the corner in Waterbeer Street. Looking into the busy workshops he seemed to recognise the atmosphere. The noise, the fumes and the heat all reminded him of the blacksmith’s forge in Winkleigh that he had grown up with. He was, after all, a country boy to whom physical labour was commonplace and the working classes were his own; with his muscular build and healthy sinews, he knew he could do this work and for a moment it even appealed to him.

The firm of Garton and King was a large and important one manufacturing a diversity of items in iron, brass and copper. Included were radiators, railings, Components in cast iron for the increasingly-popular gas cookers, and included anything which could be produced from pattern plates and moulding machines, with the accent on repetition work. The company was an old-established one. with its roots as far back as 1661 when a Freeman of the city, one John Atken, opened his ironmonger’s shop in the parish of St. Petrock, making and selling toasters, firedogs, spits and saucepans, edged tools for mechanic and husbandman, Iron and brasswork for harness and carriage, along with smaller items such as nails, hooks, chains and bolts. The firm had changed hands and working methods many times in the two and a half centuries since Mr. Atken, but it had never failed its customers and its record was a proud one. During all those years it had traded under the symbol of a hammer, the tool of the blacksmith, and ‘Golden Hammer’ was how it was best known. It took but a moment for Os to boldly approach the front office and persuade the gentleman in charge that such a firm needed someone like himself, and really, he should start first thing Monday morning if that would suit? It was the beginning of a long career for him as a foundry worker and he became skilled in the multitudinous functions of the industry. He always classed his occupation as ‘engineer’, not because he was ashamed of his trade but rather for the reason that he excelled in all parts of it.

He mastered the complexities of the pattern shop where originals of the required component were made as wooden models, slightly oversized to allow for shrinkage; he was able to mix the black moulding sand with clay in exact proportions and to introduce the compound into the ‘cope’ and the ‘drag’, the top and bottom of the moulding box. He understood and could operate the moulding machines which filled and rammed the sand automatically for continuous production, and was meticulous in his fettling and polishing of his castings. He could produce either solid castings or hollow, and terms such as ‘core-box’, ‘cope flask’, ‘riser’ and ‘hell-core’ became part of his everyday speech. The company also undertook a small amount of ‘ciréperdue’ work, the lost-wax process where the pattern is made from wax which is melted out of the moulding box to leave a replicated recess to receive the liquid metal. This procedure held great interest for Os, for he had learned from his studies that the Ancient Egyptians were masters of that delicate art form.

The work was dusty and dirty and he would repair to his lodgings at the end of a long exhausting day black and grey from the casting sand. He was fortunate however, in having found in Aunt Em an understanding landlady, and, as a routine, a hot bath and a change of clothing were his upon arrival, just before tea. He extended his hours of duty each day, usually finishing at seven-thirty, and the overtime pay was his for the spending.

Aware that his artistic abilities were in need of improvement in order to become more competent and proficient he realised the need to attend art classes but the matter of cost confronted him and he knew that he could not afford Exeter’s evening classes. The ten shillings he was paying for Exeter lodgings was not excessive but when his father suggested a move to Barnstaple where costs at the Art School 3/6d as opposed to 12/6d in Exeter and the potential of employment at Lake & Company, a reputable foundry in Newport, Barnstaple was likely then the die was cast and he moved and soon settled into the work at Thomas Lake.

This move took place probably around 1931/2. The book confirms my belief that Sam Ellacott had completed a time-served apprenticeship whilst at Garton & King, and recognising this qualification Thomas Lake Foundry welcomed his skills as there was not much he didn’t know about the industry.

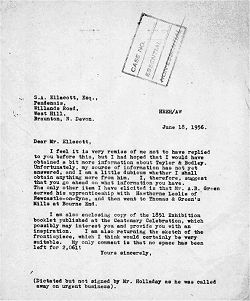

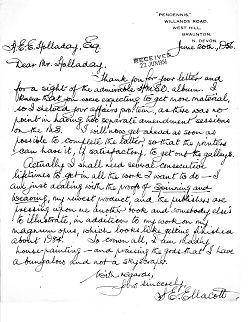

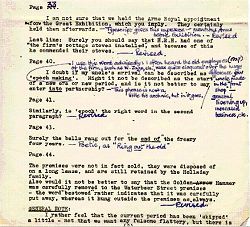

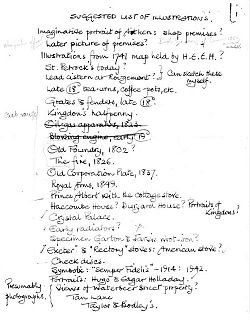

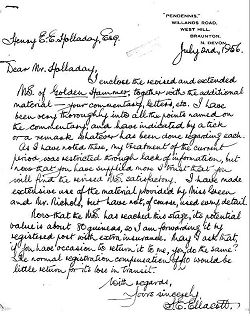

With the approach of the tercentenary of the Garton & King in 1961 I can but deduce that Henry Holladay contacted Sam Ellacott early in 1956 with a view to writing and illustrating a Commemorative Booklet, using the material and detail supplied by Henry Holladay. Much of the history had already been drafted by Nancy, Henry’s first wife back in 1939 but the War and much else had happened in the twenty plus years since then and so there was much correspondence between Sam and Henry as to the detail and wording of this proposed booklet. I have attached images of some of the correspondence between the two on this page.

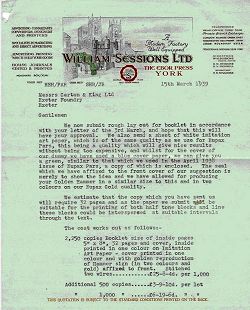

Estimate from the printer in 1939 for printing the original 1939 Notes, planned to mark the opening of the new Tan Lane Foundry and the Showroom but never printed |

The 1939 Notes actually progressed as far as receiving a quotation for the booklet’s publication and suggestions as to its layout and cover from William Sessions of York in March 1939 (above), but as we now know it did not get to the final printing stage. The Golden Hammer Booklet of 1961 was printed by W. F. Cole & Sons of Exeter and was circulated privately amongst the company’s contacts and customers. Quite how many were produced I do not know, what is strange about the booklet is that it was printed on paper, prior to folding, of fifteen inches by nine and three quarters. Even in imperial sizes it is an odd one.

Of the twenty seven known books by Samuel Ellacott, most are Methuen Outline, half a dozen local histories to do with the Braunton area of North Devon, and a novel. Golden Hammer, the History of Garton & King, seems a unique commissioned work.

|

|

|

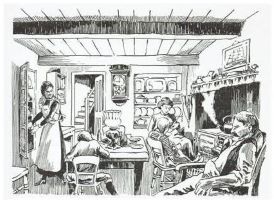

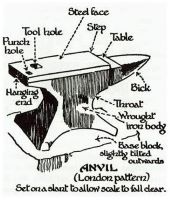

| Devon Workman's Cottage, 1914 | Anvil | Devon Smithy |

| Three illustrations by Sam Ellacott - (click image to enlarge) | ||

November 2020

Top of page

Sam Ellacott's illustrations appear in:

Golden Hammer (chapters 1-6)

In the Foundry and The Great Exhibition 1851

Sitemap / Contents