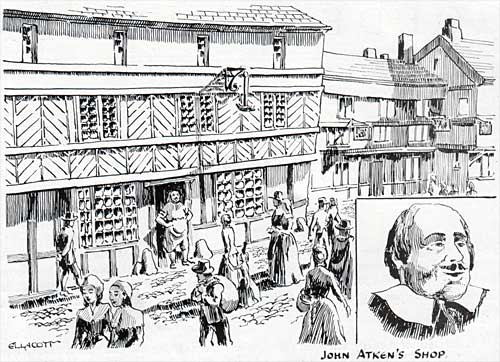

FAIR and bright was the May morning in that blessed Year 1661 as Master John Atken stood, rosy and portly, at the door of his house hard by the Conduit at the top of old Fore Street in Exeter. Cheerfully did Master John beam upon the prospect of the busy street to right and left, as his mind dwelt upon the well-stocked shop behind him, and the well-furnished living quarters above it.

A Freeman of the City was John Atken, after loyally serving his time with a worthy ironmonger of the city, Thomas Dixe by name, who was also a Freeman. Now John was himself master of a flourishing ironmongery business here in the parish of St. Petrock's. A brave selection of wares in wrought iron, brass and copper was on display in the small, heavily-framed shop windows, with their tiny panes of thick glass -- toasters, firedogs, spits and saucepans, edged tools for mechanic and husbandman, iron and brass work for harness and carriage.

Inside the shop were the greater articles in heavy metal ; firebacks and firebaskets, great pans and kettles, ornamental work for garden and park were lined tip to tempt the customer's eye. Drawers and shelves held a miscellany of smaller wares nails, hooks, chains, bolts, and scores of other such items. Great rolls of lead stood in a corner by the keg of gunpowder, for the ironmonger sold both powder and lead for casting bullets.

Though he had been but a short time in business, John's shop was so happily placed, near the junction of four streets, that a brisk trade had already rung many cheerful crowns Into the iron-bound strong-box upstairs. Small wonder that he looked with pride at the swinging sign above his head the golden hammer that he had chosen as best befitting his trade.

The narrow, cobbled street was full of signs; great and small, blazing in bright colour or weather-beaten and dingy, they swung and creaked away in perspective as far as John could see. Long before, the law had decreed that all signs should be at least fifteen feet above the ground, so that a horseman's head was not imperilled. On windy nights, the un-oiled squawking of scores of signs was as a source of fury to newcomers to the city, striving to get sleep.

On this bright morning the merry shoppers and passers-by seemed to form a gay colourful pattern of movement. John listened to the clack of the housewives' patterns, the crunch and rumble of the carriers' cart-wheels, and the shrill calling “Buy, buy, buy! What d'ye lack, what d'ye lack?” of the touting apprentices outside the drapers' shops.

Far away indeed seemed those dark days, a mere fifteen years or so before, when the Faithful City had struggled in the remorseless grip of the Puritan conqueror. Heavy had been the hand, and stern the reprisal when revolt had raged through the city – eleven good men had been hanged on one occasion. The grand old cathedral desecrated- jeering soldiers, breaking up the great organ and carrying the pipes down the street, playing upon them in mockery. Harsh decrees – nasal-voiced psalm-singing troopers billeted upon the citizens who in the black year of 1646 had been forced to give up their gallant struggle against mighty odds, with the cannon-balls of the Puritans battering, their beautiful city about their ears.

In the grey years that followed, the Lord Protector's disapproval had lain like a lowering cloud upon the city until, like a glorious sunburst, came the King into his own in that happy year of grace 1660, and all was, right with the world! ...The pealing bells, light and gay from the parish churches, booming and sonorous from the cathedral, clamoured to the heavens the boundless relief and joy of the oppressed city. Gay the decorated streets, gay the feasting, dancing citizens as fourteen dreary years came to their end.

Like a blossom in the sun, the faltering trade of the city opened out to new life. At the riverside work began on great extensions and improvements to the quay, and to the canal that had been cut in 1563, and in the uprising of revived trade the evil dream faded away.

From that shop doorway John Atken was to see many changes of scene, and the fringes of more than one nation-wide upheaval. Twenty-four years of successful trading had added a number of inches to John's girth and many a jingling guinea to his strong-box, when black-draped streets and mournful tolling of the great bell of the cathedral called to the citizens to grieve for the good-natured but self-indulgent Charles II.

“Here lies our sovereign lord the King,

Whose word no man relies on;

Who never said a foolish thing

And never did a wise one.”

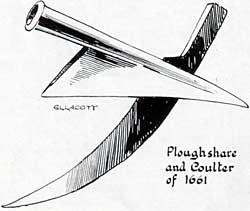

Who, on that February day in 1685, could have foreseen the great turmoil in the West Country ? Yet but a few months had passed before Charles' bastard son, new-landed at Lyme, was preaching the gospel of revolt among the sympathetic sons of the West, and the hot-headed were flocking to his support. John Atken's trade in powder and shot, and in musket and fowling piece, received a great fillip, though in truth the greater number of the unworthy 'Monmouth's rustic followers had but their homely tools of husbandry to arm them.

When the pitiful drama had played itself out, and more than two hundred men had been condemned to death in Exeter alone, Monmouth was grovelling at the feet of James II, pleading in vain for his life.

The three unhappy years of James' reign were years of depression ; his fanatical, gloomy religious outlook and savage intolerance made him far more enemies than friends, and when at last he fled, all England blessed the day and welcomed the Dutchman, William Prince of Orange and his wife Mary, James' elder daughter.

On November 9th, 1688, the Faithful City was gay with flags and bunting, and the streets glowed with the colourful crowds of welcoming citizens, for William had landed at Torbay and was to pass through Exeter on his way to London to claim the throne. John Atken closed his shop that day, prudently putting up double shutters, and thrust his ponderous belly like a battering-ram into the forefront of the cheering crowds. He added his powerful voice to the uproar as the long procession of horse and footmen wound slowly along the rainy street, to let the citizens see the Prince before he retired to the Deanery where he was lodged.

Thus life flowed with the worthy John. He was churchwarden of St. Petrock's in 1698, and soon after this, amid tokens of universal respect and regard, his busy career came to an end and he moved into retirement. Closely following him in the parish records of St. Petrock's comes the name of John Southcombe of Chudleigh, who had served his apprenticeship in Exeter - he had in fact been baptised in St. Petrock's long before - and who was a Freeman in 1690. He was to form another link in the chain of circumstance looped around the Golden Hammer.

Thus life flowed with the worthy John. He was churchwarden of St. Petrock's in 1698, and soon after this, amid tokens of universal respect and regard, his busy career came to an end and he moved into retirement. Closely following him in the parish records of St. Petrock's comes the name of John Southcombe of Chudleigh, who had served his apprenticeship in Exeter - he had in fact been baptised in St. Petrock's long before - and who was a Freeman in 1690. He was to form another link in the chain of circumstance looped around the Golden Hammer.

Next: Chapter 2

Top of Page

See also:

Timeline — St Petrocks

The Golden Hammer Sign

Sitemap / Contents