Shrewd business man as he was, John Southcombe carried on well the flourishing concern under the Golden Hammer. He had with him as apprentice one Lewis Portbury, a quick and able lad who completed his term of service in  1706, and was then, according to the custom of the time, made a Freeman of the City. This distinction was granted to any man who completed an apprenticeship in a recognised trade.

1706, and was then, according to the custom of the time, made a Freeman of the City. This distinction was granted to any man who completed an apprenticeship in a recognised trade.

It seems to have been common in the early 18th century to link the terms “ironmonger” and “haberdasher of small wares.” A modern haberdasher deals in the accessories to the drapery trade – ribbons, buttons, etc. – but in Southcombe's day any assortment of small goods was designated haberdashery. The word itself is of obscure origin ; the obsolete word haberdash expressed small wares, and was based on the Anglo-French hapertas.

Young Portbury evidently continued his work with John Southcombe, for in 1708 he married the latter's niece Elizabeth, and became a member of the family.

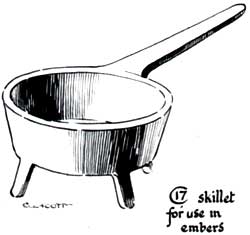

At this time most domestic hollow-ware (pots, kettles, etc.) was made of brass or copper. These articles were cast in dried moulds made of loam, a clay-like mixture, and the non-ferrous metals were used because of the founders' difficulty in getting molten iron really fluid. Brass and copper have a much lower melting-point than iron, so were more easily rendered fluid enough to make thin pots in moulds. Iron, on the contrary, could only be brought to a sluggish degree of fluidity by the methods of that time, so cast-iron articles were always thick and clumsy. The reason for this was the unsuitable fuel used in the founders' furnaces – charcoal, or in a few cases, coal.

At this time most domestic hollow-ware (pots, kettles, etc.) was made of brass or copper. These articles were cast in dried moulds made of loam, a clay-like mixture, and the non-ferrous metals were used because of the founders' difficulty in getting molten iron really fluid. Brass and copper have a much lower melting-point than iron, so were more easily rendered fluid enough to make thin pots in moulds. Iron, on the contrary, could only be brought to a sluggish degree of fluidity by the methods of that time, so cast-iron articles were always thick and clumsy. The reason for this was the unsuitable fuel used in the founders' furnaces – charcoal, or in a few cases, coal.

A few years after Lewis Portbury's marriage, he and his uncle began to notice in the district a few examples of cast-iron hollow-ware, of a thin light type never seen before. John Southcombe made inquiries, and found that the source of supply was Coalbrookdale, in Shropshire, where one Abraham Darby was using coke in his furnaces to produce very hot iron capable of pouring thin castings, in sand moulds. Darby was selling his iron goods direct from the foundry-pots, kettles, grates, and all kinds of domestic ironware at prices so low in comparison with brass that he was doing an enormous trade.

Southcombc got in touch with Coalbrookdale, a matter of several days journey at that time and arranged for supplies of hollow-ware to be sent down the Severn and overland to Exeter. It was a wise move, for the use of furnace coke spread but slowly, and Devon founders did not adopt it until well into the middle years of the century.

These increased sales of kitchen-ware added greatly to the firm's income, and when John Southcombe died, in 1724, he was able to leave Portbury a considerable fortune in goods and money The latter was already a man of consequence, having been appointed Bailiff for the City in 1719; he was also made Churchwarden of St. Petrock's in 1721. In his capable hands, the business under the Golden Hammer continued its steady progress, and at his death in 1732 it passed to his son, young Lewis then aged twenty-four, and a man of character as sturdy as his father's.

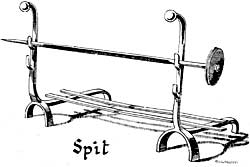

By this time it was possible to see reflected in the ironmonger's stock-in-trade several changes in social conditions. The domestic use of coal, common in London in the late 17th century was spreading westwards, and Lewis Portbury II supplied a variety of portable iron basket-grates for coal-burning, as well as built-in type coal grates. By 1740 he was selling the new hob-grates, with a small roasting-spit and two flat top-plates at the sides of the tire for resting a tea-kettle.

By this time it was possible to see reflected in the ironmonger's stock-in-trade several changes in social conditions. The domestic use of coal, common in London in the late 17th century was spreading westwards, and Lewis Portbury II supplied a variety of portable iron basket-grates for coal-burning, as well as built-in type coal grates. By 1740 he was selling the new hob-grates, with a small roasting-spit and two flat top-plates at the sides of the tire for resting a tea-kettle.

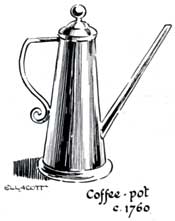

From 1700 onwards, there was an increasing demand for tea, since the wealthier people began to make it at home, where previously they had drunk it in coffee-houses. (Beverages such as coffee cocoa, and tea, introduced into England in the mid-17th century, were at first drunk in public houses opened for the purpose.) This change led to a greater sale of tea and coffee making vessels, urns and tea-kitchens.

Many people were still wary of “new mystical devices,” so there was still a considerable trade in firedogs and various types of long roasting-spit for open hearth fires. On the land, cast-iron was sometimes used.

All these developments contributed to the flow of guineas beneath the Golden Hammer. Lewis Portburv II, engrossed in the business and his public work in the city, paid little heed to the political turmoil of the times. He had been only a boy of seven when James Edward Stuart, the Old Pretender, had made his half-hearted bid for the throne in 1715 – a throne already firmly in the hands of the German King George I. At twelve years old he had heard his father, old Lewis and John Southcombe guffaw over such fools as there were who had shovelled their money into the greedy hands of the South Sea Company, whose directors fled at last and left widespread ruin behind them.

All these developments contributed to the flow of guineas beneath the Golden Hammer. Lewis Portburv II, engrossed in the business and his public work in the city, paid little heed to the political turmoil of the times. He had been only a boy of seven when James Edward Stuart, the Old Pretender, had made his half-hearted bid for the throne in 1715 – a throne already firmly in the hands of the German King George I. At twelve years old he had heard his father, old Lewis and John Southcombe guffaw over such fools as there were who had shovelled their money into the greedy hands of the South Sea Company, whose directors fled at last and left widespread ruin behind them.

Now, in 1745, Lewis looked with pitying contempt upon those half-baked Scots who were swarming and buzzing like disturbed bees over their new leader, Charles Edward Stuart. As if the power and solidity of the throne under George II could be shaken by their blatherings! Phlegmatic, he was unmoved  by the wild stories filtering through the city – propaganda, spread by those witless knaves the Jacobites, or whatever outlandish name they had – a fair young prince, beautiful in Highland dress, on a prancing white horse, leading the great Scottish advance on London, amid cheers and flowers. London taken, the king in flight – imprisoned; until, like the clear white light of day paling the lurid flicker of the fire, came the news of smashing defeat at Culloden, and the gay Prince a fugitive. Vengeance marched the length and breadth of Britain, with musket and hangman's rope, in that dread year of 1746.

by the wild stories filtering through the city – propaganda, spread by those witless knaves the Jacobites, or whatever outlandish name they had – a fair young prince, beautiful in Highland dress, on a prancing white horse, leading the great Scottish advance on London, amid cheers and flowers. London taken, the king in flight – imprisoned; until, like the clear white light of day paling the lurid flicker of the fire, came the news of smashing defeat at Culloden, and the gay Prince a fugitive. Vengeance marched the length and breadth of Britain, with musket and hangman's rope, in that dread year of 1746.

The same year saw Lewis Portbury II as Sheriff of the City, and two years later he was Mayor. To these services he added many years as a Justice of the Peace for the City and County, and- when he died, on August 13th, 1766, he gained this mention in a local newspaper, the Flying Post:-

“On Wednesday last, aged 58, died Lewis Portbury, a tradesman in whose character he acquired a handsome fortune with the greatest reputation.”

In the following June, the now famous business was arranged for disposal, and the Flying Post of the first of that month carried the following advertisement:–

“June, 1st, 1767.

To be let for a term of nine years from Midsummer next. All that dwelling house situate in Fore Street near the Conduit, lately in the possession of Mr. Alderman Portbury, deceased, consisting of a very convenient shop and passage adjoining, with a Parlour, Kitchen and Pantry behind same ; a very good Cellar under the Shop and Passage, a large Dining Room, Lodging Room, Wareroom and Closet on the Second Floor, with four Garrets over the same and a Balcony at the top of the House which commands an extensive view and a pleasant prospect of the River Exe. For which purpose a survey will be held for letting the same on Monday the 15th day of this instant June, by Three o'clock in the afternoon at the Bear Inn in Southgate Street, where the best bidder will have a reasonable price given. For further Particulars apply to Mr. Thomas Coffin, joiner, without Southgate, Exon.”

In this way closed another era.

Next: Chapter 3

Top of Page

See also:

Timeline — St Petrocks

The Golden Hammer Sign

Sitemap / Contents