A LUCKLESS wight passed under the Golden Hammer at some time after Midsummer, 1767. lie was one William Britnell, second son of a North Street brushmaker, and one-time ironmonger's apprentice. Little record remains of the hapless William's business venture, but that faithful chronicle the Flying Post displayed early in 1768 a notice offering the business to let. There was good reason – William was bankrupt. Apparently no let was arranged, and at Midsummer 1768 the Flying Post carried this advertisement:–

“Samuel Kingdon, ironmonger and haberdasher of small wares who late]y lived with Mr. Coffin in Exeter. That he has taken the house with the stock-in-trade in which Mr. William Britnell lately lived at the sign of the Golden Hammer, four doors above the Conduit in Fore Street, where he sells all sorts of ironmongery and haberdashery goods, wholesale and retail.”

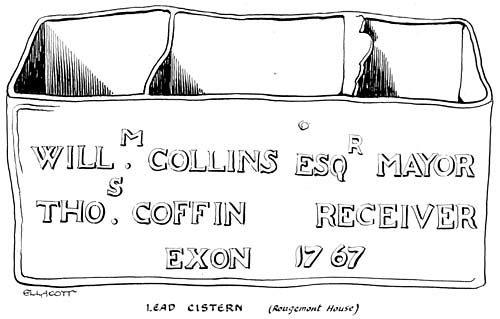

Thus the Golden Hammer was borne on by another holder. St. Petrock's church records show the progression of names-Southcombe, Portbury I and II, and Samuel Kingdon: propos, the Thomas Coffin who figures in the two announcements was the City Receiver - his name with that title appears on an old lead cistern dated 1767, standing now outside Rougemont House. As Sam Kingdon had been living with Mr. Coffin, the business had obviously been brought to his notice, and he had ventured to take it over. A dialect poem of the period mentions the firm : –

“Then us went to Maister Kingdon's---the zine o' th' Ammer –

W'ere us bought a pair o' spartacles vur poor ol' Grammer :

Vur Grammer's bline, an' can't Vurry wull zee

T'other day'er tuk an ole Jackass vur me!”

The family of Kingdon was a large one, and was very well known in the West Country. However, our business is with Samuel, who was one of a Thorverton family of eight. He served his apprenticeship in Exeter with -Mr. Coffin, and in 1768 he took over William Britnell's stock-in trade and premises. In the same year he married Jane Kent, daughter of William Kent of Oxford.

Samuel in his turn became Churchwarden of St. Petrock's, and he followed the tradition of the Golden Hammer by serving the city well in public life. Once more we are indebted to the Flying Post, for an advertisement dated June 12th, 1783 : –

“Samuel Kingdon, ironmonger, Acquaints his friends and the public in general that he now manufactures all kinds of brown tea-kitchens, coffee urns, coffee pots, etc., and new browns and repairs old ones in the neatest and compleatest manner. Any of these articles sent from the countrv to be repaired shall be immediately refitted and carefully returned.

N.B. – He also sells the patent elastick trusses for nasal [navel ? -Ed.] ruptures at 4 gns. each and for other ruptures at 2 gns. each, which are the prices the makers sell them for in London. He hath as usual a very extensive assortment of every article in the ironmongery and hardware trade with a great variety of the most useful grates, fenders, etc.”

There is no actual evidence of a factory being operated by Samuel Kingdon, but it seems quite probable that he used part of his warehouse for the purpose, hence his remark on the making of tea-kitchens. In passing, it is curious to note that newspaper names such as Flying Post, Morning Post, Mad, Herald, Courier, etc., all gain their names from their common ancestor, the news-letter, carried in a postboy's letter-bag with the mails.

The much-quoted Flying Post comes to the fore again when in the issue of early June, 1787, Sam Kingdon gave notice of an extension of his business:–

“Samuel Kingdon, ironmonger, having established a warehouse in Theatre Lane [now Waterbeer Street] to sell copper, begs leave to acquaint the public that he hath an assortment of every kind of it, which he sells on the same terms as the warehouse in London and Bristol and that he takes in exchange all sorts of old metals for which the utmost will be allowed either in exchange or in money.

He keeps as usual at his house adjoining in Fore Street an extensive assortment of all kinds of ironmongery, braziery, cutlery and tin goods. He also manufactures all kinds of grates, some of which are constructed as to render them an effectual cure for smokey chimneys.”

It seems likely that by this time the premises had been allotted a number. An Act of Parliament passed in 1767 decreed that all London street doors should be numbered for the growing system of post delivery. Soon afterwards the painted number and letter-delivery slit appeared in the provinces, on townspeople's doors, so it might well be assumed that the house of the Golden Hammer then became 190, High Street.

At this time, too, the Hammer must have been in some way incorporated into the face of the building, for the danger from insecure swinging signs had called forth an Act concerning them. All shop signs were directed to be arranged flat against the shop front, and this gave rise to the large name-board over the shop. In later times the law fell into disuse, and the swinging Hammer reappeared.

A curious relic of this period is a type of coin circulated in the city by the Kingdon family. This is the ‘Exeter Halfpenny’, issued in 1792. One side shows the Exeter arms, and the other a portrait of Bishop Blaize, the patron saint of the woollen trade, with the words “Success to the Woollen Manufactory”. Around the edge of the coin, in place of milling, are cut the words “Payable at the warehouse of Samuel Kingdon.”

One of the Kingdon family was in the wool trade at the time, and as these coins were apparently made by the firm, it is possible that Sam Kingdon had an interest in his relative's trade. An alternative reason is that Samuel issued the coins for trading purposes, and that the reference to wool was a reminder of the city's principal trade.

Ironmongers at the end of the 18th century found their trade greatly extended by the advances made in ironworking, especially in cast work. Coke was now commonly employed by ironfounders, and William Wilkinson's cupola remelting furnace produced cast iron of high quality. Repetition work for gates and railings of light and ornamental design was made possible by the hot, really fluid metal available. The invention of the cooking range in 1780 created another branch of the domestic ironwork trade. Tool steel was improved by Mushet's process of 1798, though production was limited.

Amid this upsurge of progress Samuel Kingdon died, on November 1st, 1797, and the Flying Post published his obituary:–

“On Tuesday morning died after a tedious illness supported with the patience of a Christian, Mr. Samuel Kingdon, of this City, ironmonger. He had arrived at eminence in his profession by an unremitting and vigorous exertion of his abilities which he possessed in a great degree and conducted an extensive business through a long period with honour and integrity. In his death society at large has lost a useful and active member, the industrious artist a human and benevolent patron. His family and friends will long lament his loss, to whom in each relation he was sincerely attached, for it ever contributed to his happiness in being instrumental to theirs.”

During his twenty-nine years under the Golden Hammer, Kingdon had well maintained the traditions of the firm, in his progressive outlook and his personal services to society. His successors now looked to the new century for opportunities to emulate him.

Next: Chapter 4

Top of Page

See also:

The Devonshire Dialect Poem in full

Timeline — St Petrocks

— Newspaper Ads

Sitemap / Contents