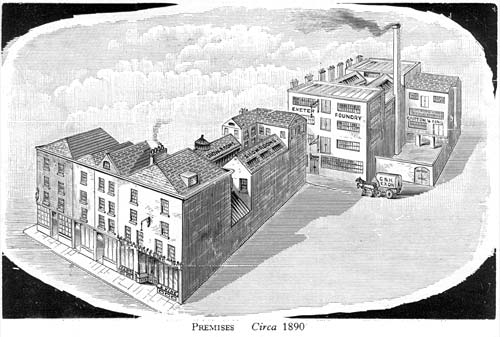

It was fitting that a firm with such great traditions should be carried on by men of ideas, and these were forthcoming in the persons of the Exeter ironsmiths, Messrs. Garton & Jarvis. John Garton was the prime mover in the alliance of these two men. He had run a small brightsmith and grindery business at Head Weir in 1831, but five years later he set up in North Street, where Ambrose Parker Jarvis joined him. The two subsequently took over premises from William Beal, near a part of North Street known as Golden Square, which is not now traceable.

This move took place in 1840, and the firm gained a good reputation for wrought-iron work, gates, railings, grates, fenders, etc. Their property seems to have been fairly extensive, with ware rooms, cellars, and lofts; a loft crane and a cellar tramway with trucks are listed in the sale notice published prior to their move to take over the Golden Hammer.

Soon after this changeover came the news of the proposed International Exhibition, to be held in 1851. The new owners announced that they would have a stand at the Exhibition, and with this in view they prepared to do the firm justice.

Soon after this changeover came the news of the proposed International Exhibition, to be held in 1851. The new owners announced that they would have a stand at the Exhibition, and with this in view they prepared to do the firm justice.

That Exhibition, and the great building that housed it, astonished the world, and far outshone the National Exhibitions held by other countries in previous years. A huge edifice of iron and glass named the ‘Crystal Palace’ was erected to cover an area of a hundred thousand square feet. It typified the advance of the iron trade, with its 4,500 tons of ironwork, including 24 miles of cast-iron guttering and 3,300 hollow cast-iron pillars.

There were six main classes of exhibit-raw materials, machinery, textiles, hardware, arts, and miscellaneous. Apropos, the profits of this great undertaking totalled £180,437, and were used to build the Victoria and Albert Museum collections.

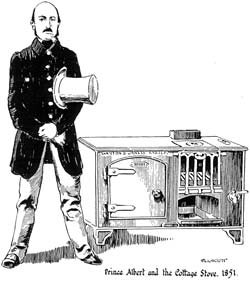

Albert, the Prince Consort, was prominent in the organisation of the Exhibition, and John Garton and his partner were delighted to hear that the Prince Consort had commended their cooking stove. His Royal Highness had a Garton & Jarvis “Cottage” stove installed in one of his Model Cottages in Hyde Park, and was pleased beyond measure by the stove’s performance. With this commendation and two bronze medals won with their stoves, the partners’ venture had been an unqualified success. Thereafter they proudly displayed the Arms of Royal Appointment.

“Moreton Hampstead.

October 15th, 1851.

Gentlemen, It is a duty I owe to the public as well as to you in expressing my entire satisfaction of the utility of your Cottage Stoves. You are aware I purchased one of them and you are aware also that I saw them at the Exhibition, NO. 3, Class 22. When I was talking to your London Agent, His Royal Highness Prince Albert was standing near and with his usual sweetness of temper the Prince deigned to tell me that he could not help being pleased with it, that he had placed one of them in one of his Model Cottages, Hyde Park, and that it answered beyond expectations. And on the score of economy let me add without a word of exaggeration, nothing I should think can excel] it for the Article in question is so studiously constructed that it is as easy as possible to cook a Dinner (in the usual period of time) for twenty men with less than a pennyworth of coal, and moreover I hereby authorise you to make what use you please of these few lines for I have penned them with the sole object of benefiting my fellow-men.

I subscribe myself, Gentlemen, Your most obliged servant,

(Signed) Isaac Billett.

To Messrs. Garton & Jarvis,

Stove Manufacturers,

Exeter.”

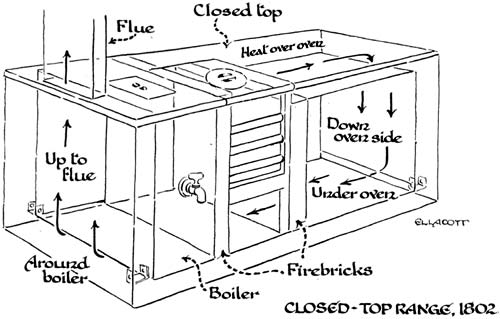

This feature of high-class stove-making was of vital importance at that time. As we have seen, the earliest modern-type coal range was introduced in 1780. The next improvement was made by George Bodley of Exeter, who produced his well-known Bodley range in 1802. During the next sixty years various other advances were made, particularly regarding the distribution of heat round the oven.

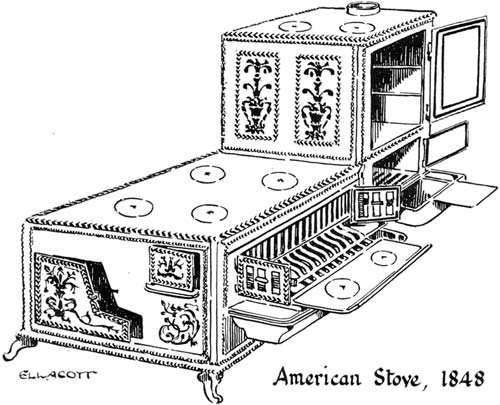

There was keen competition between British makers, and an outsider participating in the struggle was the “American Stove”, a portable unit that looked rather like a deformed china cabinet. With their traditional drive, the Americans were pushing their stoves to the utmost.

An announcement from under the Golden Hammer informed the public of the firm's success, and made it clear that “the very superior stoves and boilers had been registered to prevent piracy.” As a shattering blow at foreign competition, the advertisement modestly claimed that “one of Garton & Jarvis’ stoves is worth all the American stoves put together!”

This was a great period for ironworkers, and for Garton and Jarvis in particular. In tradition, they kept apace with improvements for foundry and smithy, and gained benefit from increased production. The old 18th century practice of drying all moulds was now abandoned, and the greater proportion of moulds in sand were poured green or undried, with a great saving of time, cost and labour. An increased output of stove metal demanded rapid production methods, which made the firm one of the most prominent West of England manufacturing ironmongers' plants.

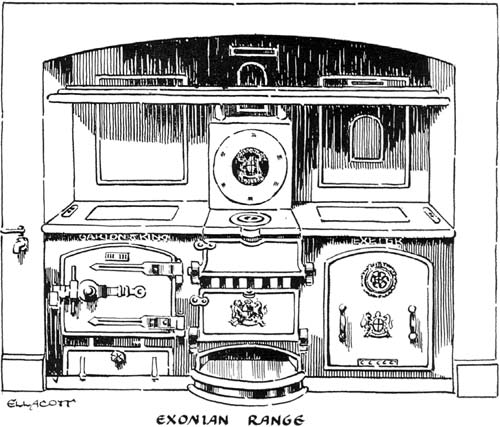

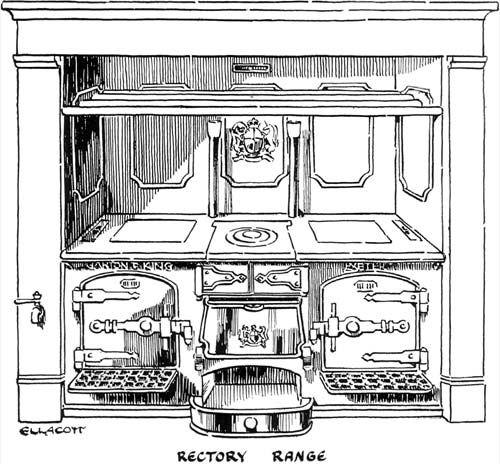

Their most famous ranges were the Exonian and the Rectory, some specimens of which are still extant. A flourishing export trade was built up by the middle of the century, and ranges from the Golden Hammer travelled the ten thousand miles to Australia and New Zealand, and to many other parts of the world. Wrought-iron work was naturally a great feature, since Garton and Jarvis first became noted for this product. Until the city suffered under the bombs, there were many fine examples of the firm's work to be seen, such as the gates of the old Exeter Bank (now part of the Royal Clarence Hotel) ; the railings around the Deerstalker statue in Northernhay, and those in front of the Commercial Union buildings in High Street.

The firm has also the highest reputation for heating plant. One of the earliest types of pipe coil radiator was produced under the Golden Hammer, as well as sectional cast-iron radiators. The sections were connected by right and left-hand threaded nipples, on the same principle as that employed to-day.

As previously remarked, the firm had been designing and making greenhouse boilers, in addition to pipe coils and radiators, quite early in the 19th century, when such plant was by no means common. The Kingdons had installed heating for greenhouse soil by means of buried hot water pipes, to perform the same function as the electric heaters of the present day. There are examples of such water-heating apparatus still in use in the Tropical House at the Botanical Gardens, Kew; they were put in by the firm in 1843.

Other work for this progressive firm was found in the slowly-increasing use of household baths and water-closets. The fitted bathtub, of quaint appearance, was installed in a few households, but most well-to-do people used hip-baths. Water-closets had been introduced by Sir John Harington, but the problem of sewage disposal was a great obstacle to their use. Even in the mid-19th century there was no connected sewage system, a few houses that were in line with a river might be so served.

By 1860, the firm of Garton & Jarvis was almost a self-contained unit, able to produce a quantity of the tools and apparatus required in the workshops, and to supply many articles for the ironmongery department. In spite of the great size of the business, the tradition of public service was maintained, for John Garton was Churchwarden of St. Petrock's from 1854.

Garton's partner died in 1865, and there came south from Barnstaple a new partner with a significant name–John Gould King. In this way the firm became renamed “Garton & King”.

Next: Chapter 6

Top of Page

See also:

Great Exhibition — Cooking Equipment — Railings

High Street Emporium — Waterbeer Street Foundry

Sitemap / Contents