SORELY stricken as she was by her great loss, Jane Kingdon was yet imbued with the dauntless spirit of the servants of the Golden Hammer. A week after her husband's death, she advertised in the Flying Post to this effect:

“Jane Kingdon, wife of the late S. Kingdon, gratefully thanks the nobility, gentry, and the public in general of this City and the adjoining Counties for the many favours conferred on her late husband in the ironmongery business, and begs to inform them that she still continues the same for the benefit of herself and family, in all its branches. Having, during her late husband's life, taken an active share in the business and now also retaining his same assistants, she doubts not of giving the utmost satisfaction to all those who will be kindly disposed to favour her with their orders and the greatest diligence and exactness will be observed in their fulfilment as in the lifetime of Mr. S. Kingdon.

8th Nov., 1797.”

At this time, Britain was locked in the struggle with Revolutionary France, a struggle that was to endure with scarcely a break for the next eighteen years. The currency regulations and other restrictions imposed by the wartime Government rendered the widow's administration of the firm doubly hard. For seven years she managed the business alone, until in 1804 she was joined by her two sons, Samuel and William. Samuel Kingdon II had begun his apprenticeship under his father. He completed it in 1802, when he went into partnership with one William Huxham in a concern styled “The Exeter Iron Company.” This alliance lasted only two years; in 1804 Samuel II entered the family business with his mother and brother, and the firm was renamed “Kingdon & Sons.”

Greatly to Jane Kingdon's credit, the business was then so flourishing that the partners decided to do away with the outside purchase of stock, as far as possible, and to develop a line of production for retail. To this end they purchased an ancient building standing in Waterbeer Street. The building was popularly known as the “Old Guildhall,” but local historians give little credit to the title, though the building was much older than the existing Guildhall.

On this site the Kingdons built a foundry, a smiths' shop, and warehouse, and by 1806 they were advertising for more foundry workers, blacksmiths and whitesmiths. In opening a foundry at this time, the partners had the advantage of the developed form of steam blast engine, of the type invented by Smeaton forty years before, with instead a blowing cylinder instead of the old-type alternating bellows blast.

Business was brisk in spite of the long-drawn-out war years. Europe the grip of the Corsican tyrant, and Britain alone stood unconquered among among Napoleon's foes. After the great Trafalgar victory, British men-o'-war held the seaways, though the army could do little for the time. Still, life had to go on in wartime Britain, and trade not war is a nation's life.

Samuel Kingdon married in February, 1805, soon after entering the firm. His bride was Sarah Eyre daughter of a Sheffield ivory merchant, John Eyre. Both brothers maintained the tradition of public service by taking a most active part in the life of the city, and their outlook did credit to the memory of their predecessors. In the year 1813, amid great admiration, the Kingdon's premises were fitted up with gas lighting, which combined, as one writer expressed it, “the twin sisters Science and Taste.”

Gas was very much in the news, following the pioneer work of the gifted Murdock-he had fitted up the steam-engine works of Boulton and Watt, in Birmingham, with gas lighting in 1802. A company founded by a rival inventor, F. A. Winsor, arranged the world's first gas lighting for streets, in Pall Mall, 1807, and in 1813 Westminster Abbey was lit by gas.

As used at that time, gas lighting was a mixed blessing. The burners were of Murdock's batswing type, with a narrow slot for the low- wide flame, and were much affected by draughts. Furthermore, the installation of pipes and fittings was carried out in a cheerfully slapdash manner, since the danger of leaks was not realised.

Jane Kingdon maintained close touch with the management of the firm, but there was no longer any need for her to take active part in it since her two able sons were there. They still deferred to her wisdom, however, and their sense of loss was great indeed when the gallant old lady died, in 1816, and was buried at Exmouth. The Flying Post, which had recorded so much of the story of the Golden Hammer, praised her merits in a kindly notice:

“Died on Friday last, Mrs. Kingdon, widow- of the late Samuel Kingdon of this City, ironmonger, whose cheerful disposition and kindness of heart endeared her to her family and friends and renders her loss lamented by all who knew her.”

With admirable unity of purpose, the Kingdon brothers weathered the difficult times following the close of the Napoleonic War. Factory owners were very awkwardly placed as regards

Continental trade at that time. The shattered countries of Europe desperately needed factory-made goods of all kinds, but they could only pay with corn, the only thing they could produce for the time. British farmers objected to the import of cheap foreign corn (they had been reaping a golden harvest in both senses of the term, during the war! The Government had to choose between (a) allowing the factory owners to sell for foreign corn the goods bulging their warehouses, and (b) protecting the farmers from a fall in prices, at the expense of the manufacturers.

Continental trade at that time. The shattered countries of Europe desperately needed factory-made goods of all kinds, but they could only pay with corn, the only thing they could produce for the time. British farmers objected to the import of cheap foreign corn (they had been reaping a golden harvest in both senses of the term, during the war! The Government had to choose between (a) allowing the factory owners to sell for foreign corn the goods bulging their warehouses, and (b) protecting the farmers from a fall in prices, at the expense of the manufacturers.

A compromise was reached, import of corn being forbidden unless home-grown corn cost more than 80s. a quarter. Of course, the wily farmer pegged the price at 79s. 11d.! However, this was only a temporary setback for factory owners; as the European countries began to recover, normal trading was resumed.

The City authorities were impelled by a new Act of Parliament to begin a campaign of improvement in street lighting, paving, etc., and William Kingdon was appointed Parochial Commissioner for St. Petrock's. Samuel's interest was in St. David's church, where he was Churchwarden for some time ; his name was engraved on one of the bells.

The march of events under the Golden Hammer was rudely checked in October, 1826, when a disastrous fire destroyed the foundry and smithy. Once again the firm's recorder, the Flying Post, provides first-hand information:

“On Saturday morning last, about half-past four o'clock, the persons living near the Manufactory of Messrs S. and W. Kingdon, furnishing ironmongers, Waterbeer Street, in this City, discovered that it was on fire on the ground floor ; at this time the flames were forcing their way through the shutters of the back front, towards and within a few feet of the extensive lofts and workshops of Mr. S. Hearn, currier, in North Street. An alarm was immediately given, the various fire-engines were drawn to the spot, the engines and a strong detachment of the 17th Lancers arrived from the barracks and a large number of every class had by this time so extended that it was with difficulty the books of the Counting House in front of the Manufactory towards Waterbeer Street were got at and preserved, and the flames bursting upward the whole of this vast building, three storeys high with an attic, extending 150 feet in length, became one immense body of fire, which, the wind being high, was vomited forth with a bellowing that strongly reminded those present of the descriptive accounts of volcanic eruptions ; completely illuminating not only the city but the horizon for miles around, and fearfully preserving the illusion by the thundering noise emitted as the floors and roof with the vast stock of machinery in all the different stages of work successively fell within the strong partition walls to the ground. By seven o'clock the Manufactory was entirely destroyed, though within its walls lay a vast body of fire which even on Sunday required the prompt aid of the engines. To the strength of these walls it is chiefly due that the destructive element was confined almost wholly to Messrs. Kingdon's premises, the damage done to the neighbouring houses being but trifling. The Manufactory was probably the most extensive in the West of England, and gave employment to upward of 250 persons, and some idea will be formed of the extent of the damage by the fact that there were upwards of 300 tons of unmanufactured material on the premises, to say nothing of the loose quantity of work, a considerable portion of which was nearly in a finished state. Messrs Kingdon were insured, but it is said to a small amount in comparison with their loss. The cause from which the fire originated cannot be ascertained ; the men have latterly worked late, but the clerk whose duty it was examined the whole premises about ten o'clock the preceding night and when he left he considered all safe. Messrs. Kingdon have nobly determined that, great as their loss may be, not an individual in their employ shall suffer; all are retained, and, while the Manufactory is being rebuilt, will be kept at work in temporary shops.”

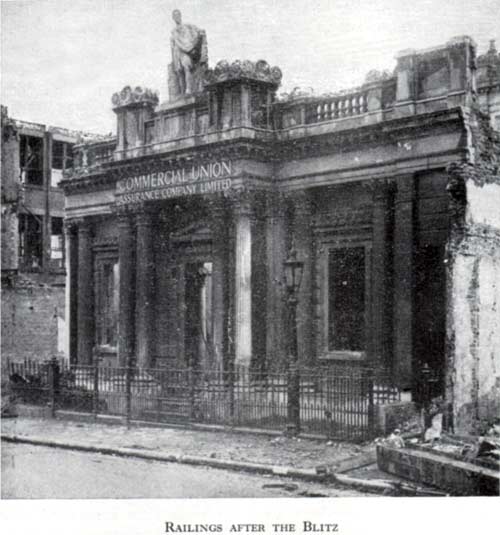

This graphic account of the disaster gives a good idea of the great extent of the firm's business at the time. There is a record still extant of the payment of £1,500 by the West of England Insurance Company, which to-day still does business with the Golden Hammer as the Commercial Union.

For over 150 years the connection has been maintained. Samuel Kingdon II was one of the original local directors of the West of England Insurance Company, and the archives of the Golden Hammer contain a copy of the original policy applying to the Kingdon premises, issued one year after the West of England Insurance Company was founded. Thenceforward the latter maintained continuous assurance coverage on that property, and this was carried on when the Commercial Union Company took over the older concern.

The business connection has always been a two-way traffic, for the Golden Hammer received a contract, which is still held, for railings and other ironwork outside the old West of England Insurance Company's premises. Though this work was demolished during the Second World War, it was fortunate that a photograph had been taken, and this is held with the contract.

When the present Commercial Union building was erected in High Street after the war, tradition was still maintained, for the contract for the electrical and domestic installations went to the Golden Hammer.

Another concern having a long-standing connection with the Hammer was the bank that served it at the time of the great fire. This was the firm of Saunders & Co., of the Exeter Bank, founded in 1769, whose direct descendant is the Exeter Bank Branch of the National Provincial Bank. The latter still does the banking business of the Golden Hammer, and the evidence seems to show that its record of service has been unbroken from the outset.

To return to the Kingdons. Such a shattering blow might have crippled lesser men, but the Kingdon brothers doggedly set to work to recoup. In the same year they bought a large block of Waterbeer Street property. These premises had formerly housed the Episcopal Charity School, which was moved to a site in Paul Street. In modern times, the Paul Street building became a Civil Defence Lecture Centre.

The Kingdon's new property comprised two dwelling-houses separated by a courtyard, covering a site of 120 ft. deep, with a frontage of 27 ft. and a rear dimension of 24½ ft. The site was quoted as having “the advantage of an approach at the back through a lane of sufficient breadth to admit wheel carriages” -later known as Trickhay Street.

Ten years of hard going, of shrewd dealing and ceaseless work by the brothers brought some of the lustre back to the Golden Hammer. The year 1836 saw the firm enjoying a measure of its old prosperity, and Samuel Kingdon - ‘Iron Sam’ as he was generally known - was Mayor of the City in that year. He was the first Mayor of Exeter to take office after the passing of the Municipal Corporations Act of 1835. This Act was directed against abuses and unconstitutional conduct by local governing bodies, whose powers had previously been very extensive.

Following “Iron Sam's” year of office, the old Corporation plate was sold, on February 8th, 1837, and it was decided to present the silver salver to him as the last Mayor to use it. On May 29th, a dinner was given at the Old London Inn, presided over by Mr. W. H. Furlong, and the presentation was made amid general acclamations. This salver must have been returned later, for it is now among the Corporation's plate.

William Kingdon also reaped his share of high public office, for he was made Sheriff of the City in 1842.

Seven years after that date, when the Golden Hammer shone with all its old brightness, and the honoured firm of Kingdon & Sons had risen clear of the years of struggle, an announcement was published as follows:–

“Retiring from business.

Messrs. S. & W. Kingdon having for some time announced their intention of relinquishing their very old established business of ironmongers, smiths and founders, have determined to offer their stock-in-trade which has been much reduced in value on advantageous terms to purchasers. To any parties possessing a knowledge of the business, combined with a moderate capital, the present opportunity affords advantages seldom met with; the arrangements decided on require immediate application. The premises, which are very extensive, will be let at a low rental. None but principals will be treated with. A steam engine of 8 h.p. to be disposed of on reasonable terms. Jan. 18th, 1849.”

After 81 years, the Golden Hammer was to see the Kingdons no more. The two brothers enjoyed a peaceful retirement, William at Haccombe House, managing his property in Colleton Crescent, and Sam at Dury ard House, similarly employed over his extensive lands in the east around St. Sidwell's.

At the time of the Kingdons' retirement, the firm specialised in greenhouse heating plant. It is interesting to note that the brothers frequently sent exhibits to shows where hothouse fruits, etc., were displayed; they evidently reaped the benefit of the skilful work of the firm's hot-water fitters.

For a short time Sam and William seem to have owned a small business in Cathedral Close. This may have formerly belonged to Zachariah Kingdon, a relative in the lacemaking and woollen trade.

The connection of the Kingdons with the woollen industry links up with the Exeter Halfpenny previously mentioned.

Sam's period of retirement was brief; he died at his house on January 14th, 1854, aged 75. He left behind him an enviable reputation as “a magistrate of the City of Exeter, beloved and respected by his numerous family and friends for the high integrity and great kindness of heart which distinguished him throughout a long and active life.”

William followed his brother on January 6th, 1858, and was buried at St. David's. The two Kingdons were long remembered for the esteem they won themselves under the Golden Hammer.

Next: Chapter 5

Top of Page

See also:

Waterbeer Street Foundry — Newspaper Ads

A Two Way Traffic — Illumination — Banking

Sitemap / Contents